Translation of the Complete Bible into the Tandroy Language

In late 2021, a 20-ft. container loaded with 20,000 Bibles, which have been translated into the Tandroy language, is scheduled to travel to Madagascar for distribution among the Tandroy people. The Bibles will travel nearly 6,000 km (about 3,700 miles) from Ebenezer printing press in Mumbai, India, by ship across the Indian Ocean and arrive in Fort Dauphin, one of the most southern port cities of Madagascar. These Bibles are the second printing of the complete translation in the Tandroy language.

Truck delivering first printing of Tandroy Bibles

How did this remarkable event, which will bring the light of the Gospel in an unprecedent way to a largely unreached tribal group of 1.3 million people, come about? It is the result of a vision experienced by one man over 20 years ago – and this is his story.

Steve’s Work in the Androy District

Steve Lellelid is a trained engineer who lives in the Southernmost part of Madagascar, the Androy region, home to almost 1.3 million Tandroy people. This is a drought stricken, harsh, forgotten land where its people live in constant want of the most basic necessities of life. Water, food, medicine and education are scarce for the once proud, warrior-like Tandroy people who live in the highlands amongst forests and plants such as the rasping hooked thorn-vine and Tamarind trees. The region rising up from the coast is mountainous and the roads are beaten tracks that weave through the forested bushlands. Villages where disease and malnutrition are common, are scattered across rocky plateaus and are surrounded by cacti, often the only food to sustain life through long periods of drought.

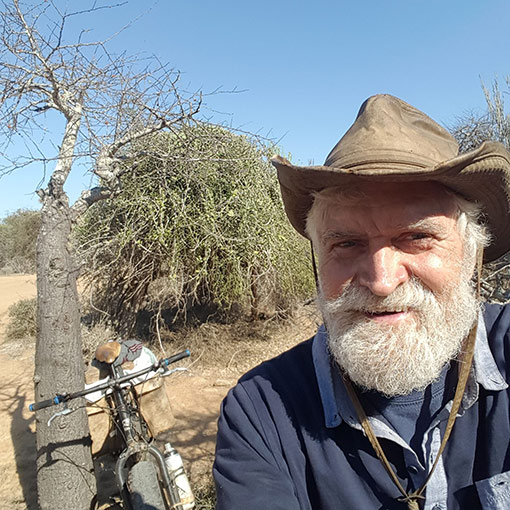

Steve Lellelid

These isolated settlements are joined by winding paths beaten out of the bush by occasional 4X4 vehicles, bicycle paths and walking trails that weave around seasonal lakes, long since dried out. Steve ascends through the hills by bicycle, entering village after village, meeting the old and shrivelled people who sit still in their pain, move slowly, or struggle alone to cajole the dry earth to produce food.

The villages have shrunk in size. It is clearly long after the young people have left to seek greater opportunities in the city, and long after the once-proud tribal demeanour of the elders had been crushed into the dust of the thirsty land.

The roads they drive on

Reaching the Mountain Villages

For several years Steve has travelled laboriously by bicycle between mountain villages, stopping at every dokany – coffee shop – along the road, where he reads from the Bible and tells people of God’s love for them. With almost no trained medical staff or services in the region, Steve carries a heavy rawhide leather case of herbal remedies and a hand-written notebook of treatments for the sick people he encounters.

The people, hungry for hope and healing, welcome Steve and the message and treatments he brings, which are more effective than the charms of the witch doctor. He hands out remedies for maladies and ailments as he is able, also encouraging the sick and elderly to maintain their own health by drinking two litres of water a day to remain hydrated so their bodies do not become like dried fruit, unable to fend off illnesses brought on by the ravages of ageing. Most importantly, Steve shares the water of life, the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the free gift of eternal life with everyone he encounters as he treats and prays for them.

A Vision for a New Translation of the Bible into Tandroy

This was the pattern of Steve’s work amongst the Tandroy people for more than two decades until the end of the 1990s. His eyes were opened in a new way when he was invited to speak in a church in the village of Nikoly, where people shed tears after hearing Steve preach the Gospel in their own language for the first time. Then later at another service in Antsakoantsoa, Steve continued to preach and read from the Bible in the Tandroy language.

Again, people shed many tears as they heard and understand the message of the gospel in their own dialect for the first time. After the service, Steve’s wife Tafisoa heard people confirm that it was the first time they understood a sermon and they were hungry for more, but could not understand the Imerina, the official Malagasy language used in church, which was different from their own Tandroy dialect.

A Vision in the Night

Then during Easter while ministering in Fort Dauphin in 1999, Steve had a vision that changed the course of his life and ministry. Steve describes his vision as follows:

“I was transported to a village in the spiny forest of Androy, where a man squatted at the door of his traño vokoke (arched hut) bedecked with all the regalia of a traditional healer, bare chested but for the necklace of charms and coins. He had silver dollars (tsanganolo) braided into his long sideburns. His gaze slowly swept the horizon, west to east and back, looking right through me.

Then the scene in the vision darkened and I saw a book, my own Tandroy/French dictionary given to me by a French AFVP (Association Française des Volontaires du Progrès) volunteer swirling around in space near enough for me to see every mark written on it.

This image was replaced by a Bible and as it came closer I could see it was my Revised Standard Version Bible that I had read daily on the back porch of that old cottage built in in a former missionary compound called Lebanon. I recognised it as my Bible by the familiar tear down the back spine.

This vision repeated itself three times and the meaning was clear: I was to translate the Bible, using the dictionary, from English into the language of this rural Tandroy man.”

The symbolism of this vision became clearer in the following days. The man represented the people of Androy who do not speak Imerina. The dictionary would be edited and vastly expanded. Numerous Bible versions and Greek and Hebrew helps would be used and many other people would be on hand to help.

The Translation Process Commences

The translation process was soon underway. At a funeral in Angoegoe, Jafaro, a major step in the translation process came to light. Steve was inside a hut with a dozen other Tandroy speaking Christians. Pastor Monja Martin handed him a liturgy in the Tandroy dialect that Steve had given him earlier and which Pastor Monja said he could not read fluently as he was only used to the Bible in the official Malagsy language.

Then another man in the hut named Arimana, who was the roaming catechist from the Bekitro region asked a question. “How can we translate Scripture into Tandroy at one locale that will also work for the people in another?” In answer to his own question, Arimana immediately proceeded to write a detailed translation guide of the various nuances of vocabulary inherent in each area of Androy, which he had come to know through his travels.

Then another brother in the hut called Tsimañohatse Calvin who was from Ankilevahare, Ambatotsivala, spoke up and made an excellent suggestion to Arimana for putting the translation guide into action. “While the local people are listening to a passage being read by Steve, they should signal when they do not understand something. Steve can then pause and use the guide on how the passage can be best rendered in the local language.”

Following this discussion, Steve was handed the collection of Bible passages that had been translated earlier that week for another funeral down in Añanakofandra, Kopoke. After reading each text to the group of Tandroy people in the hut, he looked up to see if there were any hands up or wiggling toes before continuing.

This continued through a dozen readings and many translation options. When the passage had been completely rendered into Tandroy, all was quiet. Everyone waited for Arimana’s reponse. His head was deeply bowed, but when at last he raised his head, tears were streaming down his cheeks.

“It has been done, but how was it possible?”

Steve responded. “Thanks be to the Holy Spirit who presides.”

Arimana said, “Can I have the translation?” Steve gave it to him, as well as layman’s liturgy for each of his 21 churches, and one for himself.

The influence of the Pentateuch in supporting the translation process

Some aspects of translating the Bible into Tandroy were supported by historical events. In the past in certain areas of the Androy region, some Tandroy tribes had been provided with copies of the Pentateuch (five books of Moses). Through reading it, they began to observe certain Jewish practices. For example, the Tandroy people keep the Jewish Calendar (Genesis 1:14) using the sun, moon and stars. They also observe other Jewish practices such as the dietary laws of Leviticus 11, they practice circumcision, celebrate Hebrew-like weddings and sacrifice bulls and sheep. Tandroy words have many common roots with Hebrew:

Due to the influence of the Pentateuch, the people already had a well-formed monotheistic world view. The blood sacrifices of the Old Testament were a part of their belief system that enabled them to understand the sacrificial life and death of Jesus and the shedding of His blood for the forgiveness of sins.

It has also been observed that Davidic era Hebrew characters have been chiseled into the mountains of Andringitra and Isalo and the Tandroy people hold the golden rule: Love thy neighbor as thyself (Leviticus 19:18); and are very hospitable. Tandroy men cover their heads for self-abasement before man and God (Jeremiah 14:3) and takes off sandals before entering a house or to worship (Exodus 3:5, Joshua 5:15).

Old Testament customs became entrenched in Tandroy tribal life

How did the Pentateuch and its practices become intrenched into the tribal life and customs of the remote Tandroy people? It is understood this occurred when a World Food Program called “Food for Work” was functioning in the Tandroy region. When people signed to receive food, it was observed if they were illiterate and used a fingerprint, or if they were literate and could write their name. Everyone who wrote their name was offered a copy of the Pentateuch, called the “Hake” in Tandroy.

The influence of Hebrew practices and customs has prepared the way for a full translation of the Bible into the Tandroy language. How do we reach the people in these remote villages?

Reaching the Remotest Villages with Hope and Healing

Our team goes out in pairs on weekends, sometimes for several days depending on distance. Each team carries a leather case of medicinal remedies and a reference book unique to his remedies to guide in treating. They also carry a Bible or part of it, as well as hymnals to distribute to the people.

So far, we’ve distributed unique cases of remedies with repertories to about two dozen men and women who have worked for us that they might be healers in their own communities.

Our practice is that before we treat anyone, we worship together and inform the people of the Kingdom of God and the Father who seeks a bride for His Son. Then we pray for the sick and the needs of the community.

Supporting Communities Through Work Placement Training and Literacy

Additionally, we have developed other ways to support communities. Sadly, there are no care facilities in Androy, so each community takes care of its own people who are crippled and lame. In the cities however, these people become beggars. So far, we’ve put 92 of these beggars to work, doing manual labor whatever they can put their hand to: weeding, hoeing, transplanting, excavating or breaking rock or crushing it for roads, hauling water from the river-bed, or grinding grain.

The poor, hired by Steve to do work

We also try to help those who come in from the country or the town and who are destitute due to having no rain or harvest and being unable to feed their families. If a person is illiterate, he joins those who seek manual labor. If someone is literate, we train and employ them in the office assembling remedy kits. So far, 52 women work in rural communities testing plant remedies, 12 work in the office formulating remedies, or on inventory, or taking down field data from agent reports, healing those who come in, and assembling and binding books.

For all those engaged in our programs, two hours in the afternoon are set aside each day for training the illiterate to read and write. We worship together and sing songs as well as conduct teaching from the Tandroy Bible. The shofar (ram’s horn) sounds morning and afternoon. Many have entrusted their lives to the Father to follow our Saviour.

The mid-day devotional with workers

Informal Developments Supporting the Bible Translation Process

Not all developments in this community have occurred through formal programs. For example, on the path to Lahake a young woman walking with an elderly man asks: “Where are you going?”

He says, “To worship.”

She begs “Please bring worship to us.”

This is how church in Tsiherike began.

In Longolava, two people travelling on bikes meet near Kibory-hara’e. One asks the other, “Please can you come heal my mother.” That begins the church in Añalamisandratse.

A flat tire at Belemboke results in a worker meeting and becoming fast friends with Tsiririvelo, a village chief.

A faulty tire valve results in a meeting and firm friendship with Vañombelo of Antanemiary, a traditional healer.

Interim materials while waiting for the full Bible translation

As an interim measure while we wait for the full translation of the Old and New Testament into the Tandroy language, we have created booklets containing stories from the Bible. These include Adam and Eve, the flood, the life of Abraham, the Gospels, as well as others.

These booklets serve to inform people of the major tenets of the Faith, and to equip each disciple to be a discipler. Our teams bring these Catechisms and begin the stories and leave the book with a literate person who shows interest in continuing the study with her people. We pray for new disciplers from each group, and foresee Tandroy Bibles soon replacing these catechism books.

The Second Printing of the Tandroy Bible

This project is blessed by having donors, Nathan and Jenny Carlson, to provide matching funds for the $61,000 cost of printing and shipping the second printing of 20,000 Tandroy Bibles to Madagascar. Nathan is the son of missionaries and grew up in this area of Madagascar, so he understands the importance of the Tandroy Bible.

Statements of Support

“I spent my first six years of life in Bekily —truly rocky ground in Androy. My second language at that time was Tandroy. Both my parents and in-laws worked for years in Androy. However, nothing has moved the Holy Spirit in these people as having receiving God’s word in their own vernacular as has been done with Steven Lellelid’s translation of the Holy Scriptures into Tandroy. The first printing of 20,000 Bibles was snatched up eagerly. However, in a tribe of several million, there is a thirst for more. Please prayerfully contribute to the second printing of the Tandroy Bible.” — John Toso

“Bringing the Gospel to the people of Madagascar has been a part of my life and mission since the days of growing up in Madagascar. After college and seminary, my wife Bonnie and I, returned to Madagascar as missionaries. Our term was cut short because of an illness in our family. We returned to the USA and served as pastor of Heights Lutheran Church in Roseville and Arden Hills, MN. Through the work of an organization I founded, Renewal International that recently merged with Friends of Madagascar Mission; I have worked to raise the funds for the first printing of the Tandroy Bible. Now, I am so thankful that a second printing is needed and encourage you to give generously so the Word of God may continue to bring the Tandroy people to faith in Jesus Christ.

— Pastor Morris Vaagenes

How to support this project

Please send your gifts of support for this project to: Friends of Madagascar Mission, PO Box 46381, Eden Prairie, MN 55344 or go to our website and pay through PayPal at www.MadagascarMission.org

[This article was co-authored by Rev. David P. Lerseth, Executive Director of Friends of Madagascar Mission (FOMM), and Dr. David Isaacson. Dr. Isaacson (PhD) is an Educational professional who lives in Melbourne, Australia, where he is a consultant in Business Analysis, learning design and technology. He works for educational organizations and corporations, specializing in learning design, systems training, strategic educational planning and implementation of learning management systems. He is also the chief research and grant writer for FOMM.]

Dr. David Isaacson

Want more info?

- Email the author.

- Like this article? Share it using the social media buttons below.

- Want a print copy? Click the printer icon below.

- And please rate the article!